On Christmas Day, 1940, Thomas Strickland died in Atlanta. He was 78 years old. His death certificate listed his occupation simply: hack driver, retired. A man who once farmed 40 acres of land in Forsyth County had spent the last decades of his life navigating the crowded streets of the city. A month earlier, just after Thanksgiving, his wife Lula had passed away. They now rest at South-View Cemetery, one of the oldest Black cemeteries in the South and the final resting place of many civil rights icons. Their journey from landownership to urban labor reflects the quiet resilience of hundreds of families displaced by the racial violence of 1912.1 2

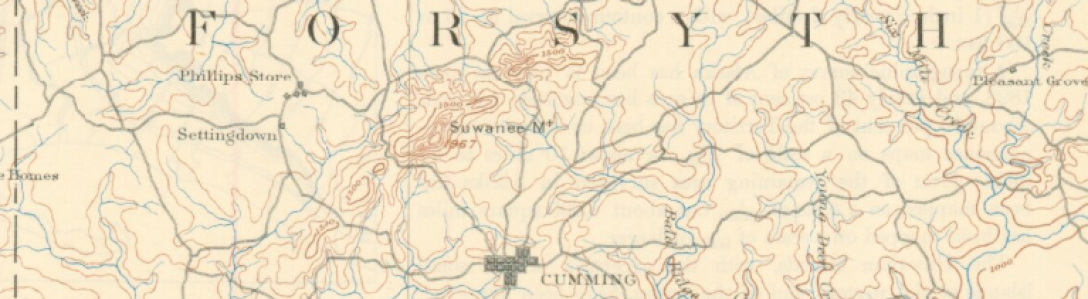

In 1910, Thomas Strickland appeared in the census as a landowning farmer in south Forsyth County. At 43, he was literate, married, and farming his own land. His wife Lula (née Hawkins) and daughter Cora lived with him. By then, Thomas had established himself among the county’s small but growing group of Black landowners, men and women who had carved out independent livelihoods in the decades following Reconstruction.3

But by the end of 1912, Thomas disappears from the county’s tax rolls.4 He sold his land in 1915 for $200 and, like so many others, left behind more than just acreage.5 What was lost was a community, a livelihood, and a rooted way of life.

By 1919, Thomas had reappeared in Atlanta. The city directory lists his occupation as “hackman”, a driver for hire, likely navigating a horse-drawn or early motor cab through Atlanta’s growing urban core.6 He lived in Vine City, a historically Black neighborhood just west of downtown. At the time, Vine City was a place of new beginnings for many displaced families. It would later become known for both hardship and historic legacy; Martin Luther King Jr. would live there decades later.7

Throughout the 1920s and 30s, Thomas continued working as a driver. He appears in the 1932 directory at 85B Walnut Street, still in Vine City. His earlier residence on Magnolia Street, and the quiet change in addresses over the years, hint at the modest but steady life he carved out in exile. Though no longer farming his own land, he continued to work, to earn, and to endure.

Alongside Thomas in both Forsyth and Atlanta was Jasper Strickland, a likely cousin, though their exact relationship remains unproven. In the 1910 census, Jasper appears immediately after Thomas, likely living on his land or nearby.3 Like many of the Stricklands, Jasper disappears from Forsyth after 1912. He surfaces in Atlanta by 1916, when he was arrested during a prohibition-era “blind tiger” raid, a term used for an illegal liquor sting.8 Jasper died young, in 1922. Thomas was the informant on his death certificate, a small but poignant signal that family bonds remained intact, even after displacement and hardship.9

Thomas’s wife, Lula, died on November 27, 1940.10 Six days after Thanksgiving. Thomas followed on December 25.11 Their funerals were held at different churches, but both were laid to rest in South-View Cemetery, a burial ground founded in 1886 by formerly enslaved Black men who were denied access to white cemeteries. Today, South-View holds the remains of civil rights leaders like John Lewis, Julian Bond, and the parents of Martin Luther King Jr.12 It is a place of memory and dignity. For Thomas and Lula, it became the final stop in a journey that began with promise on rural land and ended in a city that never fully replaced what they lost.

Thomas Strickland’s story is not one of defeat, but of persistence. Though his land was taken and his roots severed, he worked until the end. He kept family close. And in death, he joined a lineage of Black Atlantans whose lives bore witness to survival, adaptation, and quiet resistance.

Sources

- Obituary, Mr Thomas (Billy) Strickland, The Atlanta Constitution; Publication Date: 29 December 1940.

- Obituary, Mrs. Lula Strickland, The Atlanta Constitution; Publication Date: 1 December 1940.

- 1910 United States Federal Census, Big Creek Militia District, Forsyth County, Georgia.

- Forsyth County Tax Digest (1913), “Colored Digest,” Big Creek Militia District. Georgia State Archives, Morrow, GA. (No entry for Thomas Strickland)

- Forsyth County Deed Book 3, p. 599. Forsyth County Clerk of Court, Cumming, GA. (corrected deed filed Deed Book 3, p. 604)

- Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995.

- Wikipedia: “English Avenue and Vine City” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Avenue_and_Vine_City

- “In ‘Blind Tiger’ Raid Five Are Arrested”, The Atlanta Constitution; Publication Date: 31 May 1916.

- Georgia Department of Public Health. Death Certificate for Jasper Strickland, October 29, 1922. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

- Georgia Department of Public Health. Death Certificate for Lula Strickland, November 27, 1940. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

- Georgia Department of Public Health. Death Certificate for Thos Strickland, December 25, 1940. Accessed via Ancestry.com.

- Wikipedia: “South-View Cemetery” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South-View_Cemetery