Most people who drive Highway 9 know the stretch. For years it was easy to recognize in summer, when the Anderson sunflower farm turned a familiar roadside view into something worth slowing down for. Families pulled in for photos. Local memory settled onto the land like a seasonal tradition.1

It is difficult to hold that image and then consider what this same place demanded from a Black family in the fall of 1912.

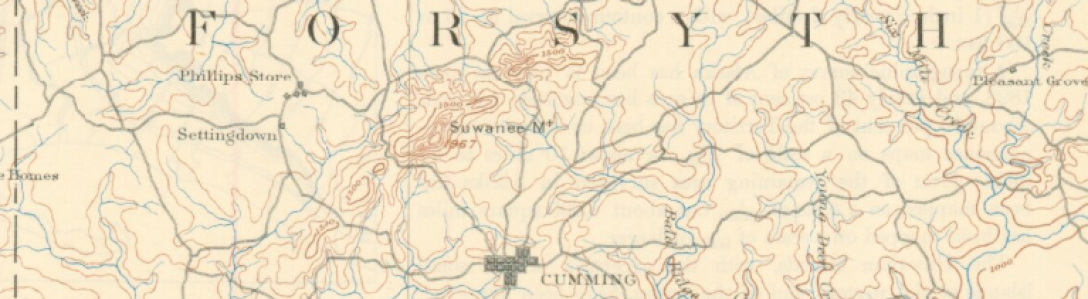

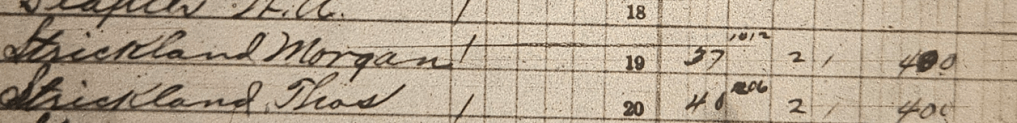

George Maxey lived here before the sunflowers and before the roadside became a landmark. His name appears in county records in the plain, durable ways these stories often do. Taxes paid. A place that can be located. A life that leaves a trace.2

One detail stands out because it is not about acreage or boundaries. It is about the inside of a home.

Twice, George Maxey borrowed money using as collateral a “Parlor organ Kimball make.”3

That single line does not explain itself. It does not tell the reader where the organ sat, who played it, or what songs filled the room. It only tells the reader that this musical instrument existed, that it was valuable enough to pledge, and that it was part of the household in a way that could be measured on paper.

It is hard not to imagine the sound of it in the house.

A parlor organ, sometimes called a reed organ, was a household instrument built like furniture. It was substantial and heavy, but it could be moved with help. People who have handled these instruments describe them as something a small group of adults can lift and load, sometimes with partial disassembly to reduce weight. Even so, it is not the kind of object that can be grabbed and carried out the door on foot. It demands planning, hands, and time.4

That is where the story tightens around fall of 1912.

By then, white terror in Forsyth County was not an abstract threat. Night riders and intimidation were not distant rumors. They were the kind of violence that pressed close and forced decisions. They turned ordinary life into a readiness to leave, quickly.

Leaving under threat compresses time. It narrows the future into a single urgent question: how soon can the family be gone.

When that question becomes unavoidable, everything in the house becomes a calculation. Not only what is valuable, but what is possible. Not only what is loved, but what can be carried.

A parlor organ is a perfect example of the kind of choice terror creates.

It mattered enough to pledge as collateral, which suggests it had real value. It was also heavy enough to slow a family down, which could make it dangerous. In a moment when speed might be safety, an object like this forces a decision that no one should have to make.

Did the family try to haul it?

Did they sell it quickly, perhaps for far less than it was worth, simply to turn a cherished object into cash and buy speed?

Did they leave it behind, not because it did not matter, but because survival required choosing smaller things?

The record does not preserve the answer. Courthouse books track land and debt. They do not usually capture the moment when a family stands in a room and decides what can be saved.

This is one reason the sunflower field matters to the story. Not because sunflowers are part of Maxey’s life, but because the present has a way of becoming a blanket over the past. A place becomes “the sunflower farm.” A stretch of highway becomes scenery. The land becomes familiar, even comforting.

Meanwhile, the earlier story is not comforting. It is the story of a person who lived and worked and paid taxes here, and then faced a county turning violent toward Black residents. It is the story of what it meant to be pushed out, and the kinds of decisions that pressure demanded.

The words “Parlor organ Kimball make” do not tell the reader what George Maxey played, or who sang along, or what became of the instrument when danger arrived. The line only preserves the fact that it was there. A real object in a real home, valuable enough to be named on paper.

It raises a question that cannot be fully answered, but should not be ignored.

When families were forced to leave, what could they carry, and what did they have to leave behind.

Today, people drive past this place without thinking about any of that. They see what is there now, or what used to bloom there in summer, and the land remains quiet. It does not announce what it once required of the people who lived on it.

The hope is that a reader can pass this stretch of Highway 9 and see more than scenery. The hope is that a familiar place can become a marker of something deeper. A reminder that this land held a life, and that the record, in a single unexpected line, leads back to the quiet brutality of that fall for the Maxey family: deciding what could be carried, and what would remain.

Sources

- Andersons Sunflower Farm Brightens-up Scenery. Forsyth County News. https://www.forsythnews.com/local/andersons-sunflower-farm-brightens-up-scenery/

- Forsyth County Tax Digest (1912), “Colored Digest,” Vickery Militia District. Georgia State Archives, Morrow, GA.

- Forsyth County Mortgage Book M, p. 400 and Mortgage Book O, p. 376. Forsyth County Clerk of Court, Cumming, GA.

- u/TigerDeaconChemist. Comment on “Early 1900s Kimball parlor organ in rural Georgia. What would owning and moving one have been like?” Reddit https://www.reddit.com/r/organ/comments/1r5nwdn/comment/o5kylim/